In testimony at her trial in 1410, the surgeon Perretta Petone claimed that ‘many women’ like her were practising all over Paris. While she may have been exaggerating for rhetorical effect, Perretta was certainly right that she was not alone as a female in medical practice. From the famous Surgeon Hersende, who accompanies St Louis on Crusade in 1250 and who would later marry a Parisian apothecary, to various Jewish eye doctors in 15th-century Frankfurt, to phlebotomists at the French Dominican nunnery of Longchamp, to Muslim midwives at the royal court of Navarre—whether they were surgeons or optometrists, barbers or herbalists or simply ‘healers’ (metgessa, medica, miresse, or arztzatin), women were almost always among the range of practitioners who offered their services in the western European medical marketplace from the 12th through 15th centuries. (Green 2008 [b] 120)

A great diversity of women practised some form of medicine throughout Europe in the Middle Ages (500-1500). Medical historians have identified a wide variety of female practitioners—from various regions, faiths, and social classes—engaged in general healing as well as specialised branches of medicine, including surgery, barber-surgery, and apothecary. Moreover, these female practitioners had the freedom and legal right to practise their healing arts. These rights were not taken away in systematic broad measures until the 14th century.

The open existence of officially sanctioned women healers came sputtering to a halt with the widespread establishment of European universities and the accompanying degrees and licences necessary to practise medicine. A licence to practise medicine as a physician could only be obtained after completing a university education—and women were banned from attending university so… that should have been that.

But if studying history has taught me anything about human nature, it’s that what is put down in the ‘official record’ is aspirational at best. Even when women were legally allowed to practise medicine, there were low recorded numbers of these practitioners in official records. Official records were documents of the activities of white Christian men—either men of nobility, men of property or merchandise, or men of the clergy. Women, like other marginalised groups such as Jews and Muslims, operated outside of the public domain of official record.

In this post, I’ll share research I’ve gathered from mediaeval medical historians who have put forward the idea that it was this very outsider identity that allowed women of Muslim, Jewish, and Christian faiths to share knowledge and spread these practices throughout Europe.

Mediaeval Universities

Universities began to be founded throughout Europe between the 12th and 15th centuries. Unlike their practice-based, hands-on, apprenticed predecessors, university-trained physicians would go through an extensive theoretical training in the classical liberal arts of theology, philosophy, and logic with an emphasis on the writings of Galen and Hippocrates—two ancient Greek scholars who believed that women are inferior to men, both physically and mentally.

These newly minted ‘learned physicians’ would have little contact with an actual human body and did not perform dissections. With the exception of Italy (which I’ll discuss in the next section) women were barred from attending these institutions; and what men learned there further entrenched the idea that women had no place in a sphere of learning at all.

So, how did we get to this female-exclusion model of learning? The simple answer could of course be basic misogyny, but there actually is a specific reason for this: In many countries, universities came about as extensions of monasteries and cathedral schools, to which girls were already not admitted. Because of this, there is a direct correlation between the Christian Church, the establishment of universities, the necessity of a licence from said universities, and then the inevitable exclusion of women from the practise of medicine.

As Achille Luchaire has adeptly argued with respect to the French situation, “the university was a brotherhood almost entirely composed of clerics; masters and students had the tonsure; collectively they constituted a church institution”. Luchaire points out that to perceive them as centres of free-thinking “is a gross error. Universities were ecclesiastical organisations and were organised accordingly”. Underlying the attempt by university-trained physicians to exclude women—and along with them Jewish and Muslim healers—from the practise of medicine, were sexist and racist theologically based ideologies and a desire among Christian male physicians to stop others, and in particular clinically experienced female healers, encroaching on their territory. (Whaley 2011)

Now we come to the Italian exception.

The Italian Exception

The Schola Medica Salernitana (School at Salerno) admitted women to study medicine. This world-famous, prestigious institution was founded in the 10th century as the first-ever dedicated medical school in Europe. In sharp contrast to what was happening with most of western Europe at the time, Italian women were able to reach a similar level in medical training to men, and accordingly bore equal rights and responsibilities.

However, Italy as a country was not a region unified in all beliefs. Northern and southern Italy differed in how they perceived women as healers and licensed medical practitioners. In northern Italy, women were recognised as physicians, surgeons, and empirics, although there were fewer female doctors in the north than the south. In southern Italy, there was a strong family trend in licensing. The daughters, wives, and widows of doctors practised medicine. (Whaley 2011)

This is odd, you might be thinking! If the seat of the Christian Church is in Italy—and the Christian Church does not promote the freedom of women—why would it be in Italy of all places where women were allowed a university education?

It has to do with how the universities were organised. In Italy, the study of medicine, at the time, resided in the Faculty of Arts, whereas Theology was a separate department. Italian universities were still under the control of the Pope, but the Church concerned itself with theological educations, and to this women were not admitted. This goes some way towards explaining why going into the late mediaeval, and even early modern period, women could have an education in several continental European universities, but not in England. Medicine was never a very popular subject in England. The brightest students vied for placements with their top law and theology programmes—the focus of English universities—areas where women would not be admitted. Perhaps if there had been a stronger medical school in England from the beginning, like there was in Italy, and if it were placed within the Faculty of Arts, maybe the situation might have developed differently?

Complexity of Spain

The situation in Spain is a little more difficult to navigate. Medical regulation in Spain was complex and started much earlier than elsewhere. The earliest set of regulations date from the years 642 and 649. Beginning in the 13th century, the Spanish attempt to professionalise medicine grew more pronounced. In 1329, Alfonso IV of Valencia introduced stringent regulations. These laws applied directly to women, ruling that “no woman may practice medicine or give potions, under penalty of being whipped through town”. Women were permitted “to care for little children, and women—to whom, however, they may give no potion”. (Whaley 2011 36) Potions really seem to be the sticking point here.

However, these rulings were issued before the Black Death came in 1346. And plague changes everything. There was a shortage of physicians in Spain, as elsewhere in Europe. Authorities in several countries relaxed some of the licensing laws which enabled women, Muslim, as well as Jewish physicians to practise medicine legally. Among these physicians we can find a number of Muslim women, described as metgesses, who served the Muslim and Christian populations as midwives, physicians, and surgeons. Muslim women also worked in Spanish hospitals during the Middle Ages. Their work went beyond nursing, as one record indicates bone-setting a fracture, and they were paid for their work.

After the Black Death, in 1363, the Cortes de Monzón (Catalan Courts of Aragon) provided an alternative licensing procedure for Jews and Muslims who, like women, were barred from Christian universities. Female Muslim women practitioners practised midwifery, surgery, and general medicine. A Muslim healer named Cahud practised medicine in the royal household of Valencia, while other Muslim women performed surgery in Barcelona. The king ruled that these women could sit an examination set by licensed surgeons and, if they passed it, they were permitted to practise.

In the 15th century, Castilian royalty, most famously Ferdinand and Isabella, always used Jewish physicians. In addition, Jews worked as physicians for many cities of Spain. The fact that Jewish women of Spain were able to become licensed physicians, and not merely ‘wise women’ or practitioners of domestic medicine, is surprising given the attitude towards women in Spain at this time and their almost non-existent official education. Perhaps it is the fact that they were Jews, and therefore outside of mainstream Spanish Catholic systems, which gave them more freedoms.

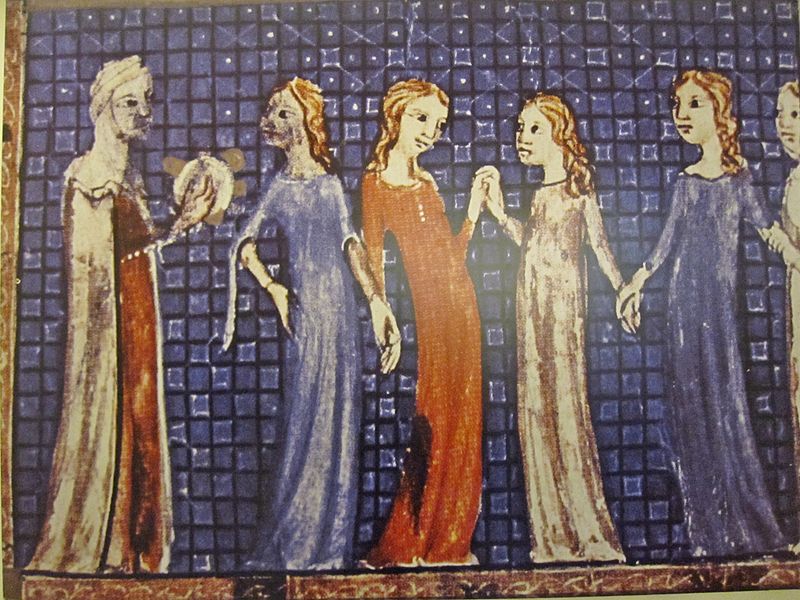

“And Miriam took a timbrel in her hand. (Exodus 15:20). Sarajevo Haggadah, Barcelona,

Manuscript on parchment, Spain, 14th Century. The National Museum, Sarajevo

In general, medicine and law were almost exclusively in the hands of Christians, not including converts, who were treated with a fair measure of distrust. However, with the shortage of male Christian physicians, these minorities, including women, were permitted to practise until the end of the 15th century.

Although Christian Spain rejected Muslim culture, Morisco medicine—that of the Moriscos and Moriscas, former Muslims who had ben forced to convert to Catholicism between 1502 and 1526—was held in high regard and both male and female medical practitioners treated members of the Spanish upper class, including King Philip II. What made the situation a bit hypocritical were the views held by Christian clergymen on Moriscas (female converts to Christianity) whom they perceived as sexual, exotic, and as demonstrating a refusal to assimilate.

In 1609, Philip III ordered the expulsion of Moriscas from Spain and directed those who were going to non-Christian lands to leave behind children ages seven and younger. It is estimated that about 300,000 people left Spain at this time, about 5% of the total population. (Whaley 2011 147-148) This was a horrible devastation, not only to the Morisca people of Spain, but also to the communities where they played a vital contribution.

As time progressed, as one would imagine, Morisco medicine became increasingly marginalised; but Jews, Muslims, and Christians had made Spain their home for centuries. This knowledge does not merely disappear. And despite their expulsion and erasure from official record, ‘unofficial’ female Muslim healers remained in the Spanish countryside. As a rule, their patients were female and healing was often a second job. However, these women did not necessarily practise their healing arts for payment. They would stop their activities on Thursday evenings, just before the Muslim holy day.

A considerable contribution was made by Arab female healers throughout Europe in the Middle Ages—and arguably most of this knowledge came through Spain. Spain had a considerable Muslim as well as Jewish minority population. Jewish physicians, both male and female, made substantial contributions to medicine in the mediaeval period. They became particularly skilled in treating diseases of the eyes and ophthalmology was often their speciality. Indeed, there were many female Jewish doctors who treated diseases of the eyes. The Jews were also often proficient in many languages—Greek, Latin, Arabic, and Hebrew—and thus were able to read and translate a wide range of medical texts. This meant that they tended to be a more educated group of physicians than their Christian counterparts. In spite of their skill and expertise, Jews suffered from persecution and prejudice. (Whaley 2011 22-23) Many women in both Arab and Jewish communities practised medicine in some form, and were not strictly confined to practising within their own communities.

Jewish, Muslim & Christian Intellectual Exchange Between European Mediaeval Women

There have been many studies into European mediaeval women and gender, however these studies mostly focus on mainstream Christian women. There is a practical reason for this, not that historians simply don’t care. If you’re an English-speaking historian, much of English-speaking mediaeval women’s history has focused on texts that can be read in English: texts from later mediaeval England. However here, contact with Muslims was always rare and where no Jews—at least any who would dare go on record as being Jews—would have been found after their expulsion in 1290. So, if we were to focus on England as our site of research, the evidence would be quite light on the ground. This is why this study looks at continental mediaeval Europe.

Just as there have been previous studies on mediaeval women, there have also been many studies exploring cross-faith interactions in mediaeval Europe, but rarely with a focus on the women of these faiths. The question of how women fit in has rarely been raised, aside from looking at the function of women (particularly prostitutes) in the transactions (real or feared) between men. Through the work of both Monica Green and Leigh Whaley, here we will look at both: at women in mediaeval Europe, the cross-faith interactions between these women, and raise the possibility that religious boundaries may have functioned differently for women than for men.

By delineating the possible social and physical spaces in which mediaeval women may have interacted, and by suggesting some types of sources that might be creatively employed to illuminate what transpired in those spaces, we hope to identify the question of women’s interfaith interactions—and the possibility that there might be some uniquely gendered components to those interactions—as an important and fruitful line of research. Obviously, we need to recognise women as the active creators of their own cultural traditions within their respective religious communities and, no doubt, likely defenders of the lines of difference. Surely it was most often women themselves who defined and perpetuated faith-defined traditions of how to prepare meat or bread, how to welcome newborns into the world, and how to prepare the dead for burial. In looking beyond wars, expulsions, and public debates about theology, we see that there were many spaces—physical, social, perhaps even emotional—that mediaeval women of different faiths may have cohabitated. There may have been potentially positive and helpful (or at least mutually beneficial) interactions. But we need not romanticise and imagine that women were universally supportive of each other. The issue, rather, is to document women in the first place and to see them as agents in negotiating how individuals, families, and larger groups constructed religious and cultural differences in mediaeval Europe. (Green 2008 [b] 117-118)

To begin with, we will only find such interactions in places where Christian, Jewish, and Muslim women cohabitated. Southern Italy, Spain, and the eastern Mediterranean created the greatest opportunities for interaction and exchange with Muslims. Jewish-Christian contact would have been even more prevalent, with small communities of Jews scattered throughout most of Western Europe; since they didn’t live in exclusively Jewish communities, some degree of interaction with their Christian neighbours must have been constant.

Slavery is another very obvious social relationship that would necessarily have brought women into dialogue across both ethnic and religious boundaries. In his 1990 study of female slavery in Genoa, northern Italy, Michel Balard found that women make up 62.9% of slaves in the 13th century, 65.5% in the 14th, and an astounding 85.5% in the 15th century. Most of these female slaves worked as domestic servants, which would probably have put them under the direct authority of their female Christian owners in the latter’s role as household manager. Neither Balard nor Susan Stuard, in her 1995 panoramic overview of the feminisation of late mediaeval slavery, explicitly explored the interactions that slavery would have created among women. (Green 2008 [b] 112)

There is an urban bias to this study, as most European Jews after the 12th century lived in urban communities. But focusing on cities is helpful because we can look at the layout of a mediaeval town to see where women might share space: wells and water-pumps, communal ovens where they would bake their bread, or even sharing certain responsibilities of minding young children: all these may have been likely physical and social spaces where women’s worlds intersected and overlapped.

Green acknowledges, though, that in an initial assessment of these possibilities, the evidence is found to be conflicting. For example, Jews may well have kept their own cisterns or wells rather than using a communal fountain. However, the more we look at basic day-to-day needs, the more we find women crossing lines of religious exclusionism.

Medicine in general was an area where there was a considerable amount of cross-faith interaction. At least in Southern Europe and the Rhineland, Jews, both men and women, made up a significant portion of medical personnel, in some urban communities as much as half. Did that same willingness to accept medical care from practitioners not of their own faith extend to the especially intimate care involved in childbirth? At least at times, it did.

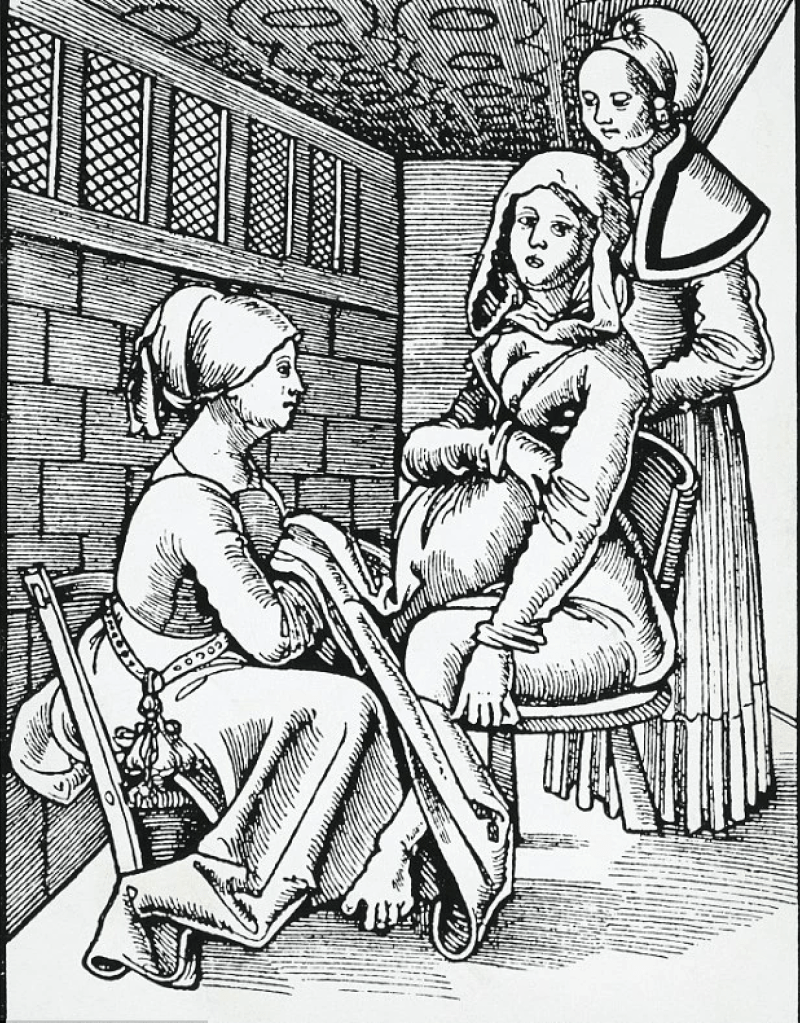

In certain contexts, Muslims and Jews were seen to provide more specialised obstetrical care than was on offer in Christian communities. Specialised midwives seem to have existed in Jewish communities earlier than in Christian communities, where it was only around the late 13th century that we see women taking on the specific occupational title of ‘midwife’, and only in the 14th century that we find the beginnings of licensing.

Among Jews, there were no rabbinic prohibitions against using Christian or Muslim midwives, or at least not if they were nor left alone with the women giving birth. Similarly, Green found no Muslim prohibitions. There were, however, Jewish bans on their own women assisting gentiles and, conversely, Christian prohibitions against Christian women acting as midwives to Jews. In both cases, there seems to have been concern that midwives not assist bringing into the world people not of their own faith. Still, it is surprising that there were not any explicit Christian prohibitions against the use of Jewish midwives, since Christian concerns about the fate of the newborn’s soul and the need to regulate baptism were growing in the same period.

To bring back the point I made in the introduction about the ‘official record’ being more aspirational than accurate, I’ve found some rather amusing historical moments of hypocrisy between the official record and actual practise:

- Jewish doctors had to deal with restrictions through papal bulls and royal ordinances which forbade them to treat gentiles. Nevertheless, their services were used by high ecclesiastical figures such as bishops, popes, and kings.

- There were three Jewish midwives practising at the Christian court of Aragon between 1368 and 1381. Household records of the court of King Carlos III of Navarre (r.1387-1425) produced evidence for three midwives working at that court: Blanca Sanchiz, a Christian, and Marien and Xenci, both of whom were Muslim.

- Indeed, when it came to concerns of bodily welfare, even the staunchest opponents of cross-faith contact could compromise. One of the first things that Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros (1436-1517) did after the fall of Granada was to prohibit, under pain of excommunication, the use of Muslim parteras (midwives) by Christian women. Yet when he himself fell ill a few years later, he was willing to accept a muger morisca (‘Moorish woman’) to cure him.

- In the 16th century, popes Paul IV and Pius V prohibited Jews from practising medicine on Christians, but this regulation does not seem to have been enforced and, indeed, many popes had Jewish physicians.

I’ll close with this remarkably vivid rare snapshot we have of life in 12th-century Sicily captured by a contemporary Muslim observer:

In trying to piece together the background of a 12th-century Latin cosmetic text from southern Italy that ascribed certain practices to ‘Saracen’ women (‘Saracen’, in the Middle Ages, is any person—Arab, Turk, or other—who professed the religion of Islam), Green found an intriguing statement by a contemporary Muslim observer, Ibn Jubayr (1145-1217), who noted with some surprise in 1184 how eagerly Christian women in Palermo, Sicily adopted the customs of local Muslim women:

The Christian women of this city follow the fashion of Muslim women, are fluent in speech, wrap their cloaks about them, and are veiled. They go forth on this Feast Day [Christmas] dressed in robes of gold-embroidered silk, wrapped in elegant cloaks, concealed by coloured veils, and shod with gilt slippers. Thus they parade to their churches bearing all the adornments of Muslim women, including jewellery, henna on the fingers, and perfumes.

I appears that in 12th-century Palermo, Christian women were looking to their Muslim neighbours as models and inspiration for beauty and fashion on a feast day when they wished to feel their most elegant. From this account, we can see proof that there was some sharing of ideas between women of different faiths, so much so that there is evidence of respect and emulation. Surely, some form of dialogue existed among these women.

Alex Metcalfe, an expert on Sicilian Arabic, translates the statement that the Christian women ‘are fluent in speech’ as ‘they are eloquent speakers of Arabic’. This puts forth a picture that they not only shared fashion, but shared language. (Green 2008 [b] 106)

Could women have been at the leading edge of the normalisation of relations between Sicily’s Muslims and their Christian overlords? There is not enough research into this to say with certainty, but it is an intriguing idea.

Sources and further reading…

Cohen, Esther, The Crossroads of Justice: Law and Culture in Late Medieval France (Belgium: E.J. Brill) 1993. Book.

Green, Monica H., Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology, (Oxford: Oxford University Press) 2008. Book. [a]

— ‘Conversing with the minority: relations among Christian, Jewish, and Muslim women in the high middle ages, Journal of Medieval History Vol 34, 2008, p105-118, Journal. [b]

Hughes, Muriel Joy, Women Healers in Medieval Life and Literature, (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press) 1968. Book.

Whaley, Leigh, Women and the Practice of Medical Care in Early Modern Europe, 1400-1800, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan) 2011. Book.