Why do the dead return? Why, in the darkness of the night, when all activity has been reduced to a trembling in the distance, do the dead disavow their rest and return to the living? Those who pass from the land of the dead to the living carry with them the promise of a place to come, and that place is haunted. –Dylan Trigg

We love our ghost stories. We love to share them, analyse them, hunt for them, and hopefully even capture them with our cameras. But therein lies the troublesome aspect of ghosts—because our search is the pleasure, there is no joy in the answer.

There is in an excitement in these feelings; as a child, many of us remember the sudden horror, then the thrill, of walking through a cemetery and imagining a hand creeping out of a cracked grave. Or walking through an old ruin, forgetting the heritage of the place to instead imagine deep tragedies of our own invention, wishing for glimpses of the ghostly Grey Ladies who cry for justice amongst the stones.

Of all ghostly apparitions we love to share and tell again, in British folklore nothing tops a lone Grey or White Lady. The Lady is the recurring ghost of a woman, usually one who has died from either having been murdered by a lover or committed suicide due to a lover’s betrayal—sometimes she might have died in childbirth or perhaps both she and her children met a violent death, but betrayed by doomed love is preferred. Although named ‘Grey Lady’, this ghost can also appear dressed in long, flowing gowns of black or brown. Rarely, there are even cases of Orange or Blue Ladies, but they have no place in a classic ghost story.

For top gothic atmosphere, we like our ladies Grey or White. Although these Ladies are not dangerous, there are tales of them hovering next to a sleeping person and whispering her sad tale into their ear. According to some legends, her story is so tragic that the person wakes and, while still wearing their night clothes, walks directly to the nearest cliff and jumps forthwith. These are the sorts of tales you’d tell around a campfire, inventing new details, relishing your own ghoulishness. But most tales of the Grey Lady are benign. She is a figure who, if anything, is pleading for help.

As Jane C. Beck observes in her seminal essay on White Ladies in Great Britain and Ireland: ‘Of all of man’s traditions and beliefs, his acceptance of ghosts is perhaps the most strongly rooted. Many educated individuals, coming from all walks and stations of life, continue to believe in, or at least entertain, the possibility that the dead may return to the living. This is probably due to man’s desire to find some shred of evidence to prove his immortality—some proof, no matter how macabre, that his identity will be preserved beyond the grave.’ (1) There is a tension between our human desire to believe that we live on beyond the grave, but a horror at believing that we do. The common tale of these trapped spirits we call ‘ghosts’ is that they are searching for rest, but they can’t rest until a specific task is accomplished or truth is revealed—which always has to be accomplished/revealed with the help of the living. One consistent throughline throughout ghostlore is that these ghosts are on a mission. A ghost without a mission is probably not a ghost at all but actually a faerie. (2)

(Jane C. Beck shares some wonderful tales of both White Ladies as ghosts and White Ladies as faerie spirits in her essay cited in ‘Sources & further reading’ below.)

We fear ghosts, so we recoil from them; but at the same time we seem to know that they need us in some way. We’ve created a belief system around these apparitions that, on one hand, makes them creatures of utter pathos, locked as they are in a cycle of impotent inaction, yet also terrifying, chasing away the very instruments of their salvation. Who would invent such a twisted system? Our relationship with ghosts is at war with itself. We need desperately to believe that they exist, but they seem desperate to complete their missions to cease their existence. Why would this form of afterlife be preferable to the peace of nothing? Who would wish for such a state? If we are searching for proof beyond the grave as a form of comfort, we will find no comfort here.

Gothic Uncanny

Our wish to believe in ghosts, sitting alongside the horror of that belief, traps our mind flickering between two states of thought like being stuck between channels. This places our love/fear of ghosts within the unsettling space of the uncanny.

Encounters with Grey Ladies represent a moment of apprehension, rather than outright terror. The uncanny inhabits a liminal psychological space of inbetweenness. It exists in our peripheral vision and is built on uncertainty. When we say to ourselves, ‘Did I just see…?’ The moment our imagination is satisfied into certainty—whether that be certainty of safety or of horror—the moment ceases to be uncanny.

Ghosts lie within the classic gothic landscape, and the gothic must always reach towards what cannot be spoken. ‘[The gothic] can gesture towards the sublime, towards the blasphemous, or towards the magical, but it must never fall into the prosaic. […] If the gothic can be explained, it is no longer gothic.’ (3) Human nature has an active curiosity that drives engagement with the darkness—and within the darkness, melancholic whimsy may find ghosts.

Shadow Angels of Silence

In the form of the Grey Lady, the ghost manifests a clash of ideas. The Lady as a ‘woman’ is representative of home, but she is out of place. Either haunting a home that no longer belongs to her, or a ruin that is no longer a home. We fear her, but why? Her story is inevitably tragic, and the double anguish of her fate is that she is then cursed to forever be locked in place reliving that very tragedy. What otherworldly judge would victim blame to such an extreme by inventing such a fate? And why do we relish so much the belief that such awful judgement makes up the clockwork of the universe? We are a twisted species indeed with our conflicting desires, making a hell for ourselves wherever we can.

Within her silence, the Grey Lady invites lean-in questions, but she embodies at once our love of investigation alongside hints of punishment for this curiosity. There is a link here too between the feminine and silence. The Victorian trope of the perfect woman, the perfect wife, as the Angel in the House, was a two-dimensional image of ‘woman as concept’. The Angel of the House was modest, pious, devoted to her children and her husband and her home, eschewing all personal desires to serve the high trinity of these more valuable pursuits. She is beautiful, perfectly poised, and—the most attractive attribute of all—silent. Within silence, the dominate personality in this conceit can write and infer any identity and story for her that they wish. Her internal world is not a real thing to be shared, but a whimsical curiosity to be imagined. If the Angel in the House is the Victorian female ideal made flesh, the Grey Lady is the female ideal made shadow.

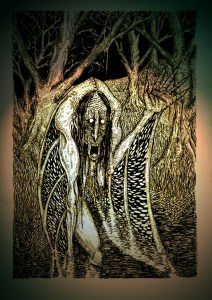

Not all paranormal women are shadow angels. There are some distorted and terrifying apparitions, such as the Gwach-y-Rhibyn, a kind of Welsh banshee thought to be the very personification of ugliness, with torn and dishevelled hair, long black teeth, withered arms and claws, and wings of a leathery and bat-like substance. (4) But the Grey and White Ladies are always beautiful—or at least fair enough in form to infer as much underneath their veiled faces.

Foremothers of the Lady

Our modern idea of the Grey Lady as mystery actually has its roots in Christianity. Mediaeval Christian belief held Purgatory as a permeable place, souls could come and go to communicate important messages and complete their missions of unfinished business. A belief in the sprit world was not incongruous with Christian belief; in fact it was an integral part of it. It was only after the religion’s evolution through the Early Modern era into Protestantism that Purgatory was done away with, and along with it its church-sanctioned ghosts. However, before our modern Grey Lady, there was a long-held belief even older than this—the White Lady. As Christianity swept across the British Isles, subsuming a heritage of animistic folklore belief under its monotheistic tidal wave, the Mother Goddess became distilled and split into the virgin and the whore. The original Mother Goddess and Water Goddess manifested as White Ladies of the faerie belief structure, representing the female pantheon in miniature. It is due to this many-faceted personality that we find that the White Lady of today can be both malevolent and benign. The White Lady harkens back to an older time and perhaps the power she once held as a deity is now manifested in her melancholic beauty.

Originally, the White Lady probably had no ghostly characteristics whatsoever. It seems that she has been degraded from her previous form as the Mother Goddess, to then a form of faerie, and finally to a ghost. ‘Today, her deified heritage forgotten, she has been sucked into the quicksand of modern ghostlore, a quicksand fed by a multitude of ancient and diverse traditions. Her older characteristics have been merged and all but lost in the ghostly spirits of a returning dead woman. Nevertheless, she has been bequeathed certain characteristics to the White Lady, characteristics that even today remain as clues to her origin.’ (6)

There are folkloric links between White Ladies who appear to have started out as faeries, then changed through retelling into ghosts, and many of this type of faerie-cum-ghost ladies are connected with wells and water. The most common fate of a water-bound White Lady is drowning; she then entices her living victim to throw themselves into the sea, river, or pond and drown themselves—bridging the gap between the faerie’s (or water sprite’s) association with water and the ghost’s earthly sorrow. However, while there are tales of faerie White Ladies in Wales and Ireland, the majority of our British and American Grey and White ladies are the trapped souls of human women. And because of their once-humanity, we identify with them in a way we wouldn’t with a water sprite. Our fear is tempered with empathy. This empathy leads to further retelling of her story and, thus, the Grey Lady is seen everywhere, while the White Faerie eludes us in her remote water-bound woodland.

Last words

There are no answers here in this short essay. Instead, I’d like to start a discussion. Why do we prefer a possible future to be tragedy-locked in place by horrid events? To be made silent and desperate as our material world disintegrates to a ruin around us, rather than believe we simply die and end when we are laid in the earth?

Like most people, I say I don’t believe in ghosts. And yet, I sort of, kind of, do—in the way that at 2am awoken from our sleep we all find horrors in our hallways. Is it silly? Most probably. But there is something stubborn about ghostlore, and of the things we ‘don’t believe in nowadays’ we do rather believe in the end.

As tragic as the story of our Grey Lady is, we want to believe in her. We want to live in a world that has secrets yet to be unveiled. When we were children, all the world was a puzzle of secrets to be unlocked. As we get older, things become too known, we are victims of our own quests for knowledge, leaving us in the rather prosaic world of answers. I don’t want to stop looking for mystery, and so I will continue to see Grey Ladies amongst the stones.

Footnotes

1) Beck, Jane C., ‘The White Lady of Great Britain and Ireland’, Folklore, Issue 81, Number 4, 1970, p.292

2) Faerielore is a complex study in itself beyond the scope of this short essay; however, to learn more I highly recommend reading Beck’s original essay on the relationship between ghost Ladies and faerie Ladies.

3) Wolfreys, Julian, Victorian Hauntings: Spectrality, Gothic, the Uncanny and Literature, (Basingstoke: Palgrave) 2011. Book. p.3

4) Seleucus, ‘Folk-Lore of Wales’, Notes & Queries, No. 19, Saturday, March 9, 1850 A Medium Of Inter-Communication For Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, Etc. (accessed via Project Gutenberg)

5) Owens, Susan, The Ghost: A Cultural History, (London: Tate Publishing) 2017. Book.

6) Beck, Jane C., ‘The White Lady of Great Britain and Ireland’, Folklore, Issue 81, Number 4, 1970, p.306

Sources & further reading:

Beck, Jane C., ‘The White Lady of Great Britain and Ireland’, Folklore, Issue 81, Number 4, 1970, 292-306

Brown, Sarah Annes, A Familiar Compound Ghost: Allusion and the uncanny, (Manchester: Manchester University Press) 2012. Book.

Castle, Terry, The Female Thermometer: Eighteenth-Century Culture and the Invention of the Uncanny, (Oxford: Oxford University Press) 1995. Book.

Chainey, Dee Dee, A Treasury of British Folklore: Maypoles, Mandrakes & Mistletoe, (London: National Trust Books) 2018. Book.

Freud, Sigmund, The Uncanny, 1919. Essay.

Grimes, Hilary, The Late Victorian Gothic: Mental Science, the Uncanny, and Scenes of Writing, (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited) 2011. Book.

Jentsch, Ernst, On the Psychology of the Uncanny, 1906. Essay.

Norman, Mark; Norman, Tracey, Dark Folklore, (Cheltenham: The History Press) 2021. Book.

Owens, Susan, The Ghost: A Cultural History, (London: Tate Publishing) 2017. Book.

Royle, Nicholas, The Uncanny, (Manchester: Manchester University Press), 2003. Book.

Trigg, Dylan, The Memory of Place: A Phenomenology of the Uncanny, (Athens: Ohio University Press) 2012. Book.

Wolfreys, Julian, Victorian Hauntings: Spectrality, Gothic, the Uncanny and Literature, (Basingstoke: Palgrave) 2011. Book.

Absolutely fascinating! Thank you

LikeLike