Everyone can identify with the desire to protect our homes. Today, we might use alarm systems or family dogs to keep our domestic spaces safe from human predators, but our ancestors’ fears weren’t only for these terrestrial threats—they felt that their homes could come under attack from unseen forces as well.

The following is an excerpt from a talk I gave at the Museum of the Home (formerly the Geffrye Museum) in November 2019, ‘Witch Bottles & Worn Shoes: Home Protection Folklore Practices’.

While nowadays we might not jump to supernatural explanations for the fears we have, we still might entertain supernatural ideas in a vague way. Anxieties about our homes can lead even pragmatic people to think magically, to perform private rituals to restore a sense of harmony.

You’ll know what dormant fears I’m talking about if you’ve felt something suddenly terrifying about your dark windows late at night after watching a scary movie. Fear can make our minds play tricks on us and is our most primal motivator.

Our ancestors left behind numerous clues in the buildings that we continue to live in today of how they attempted to protect their homes and families over the last five hundred years. Hidden within our walls and rafters there remains the evidence of magical house protection—just waiting to be exposed by demolition, renovation, or repair. (Davies, Houlbrook)

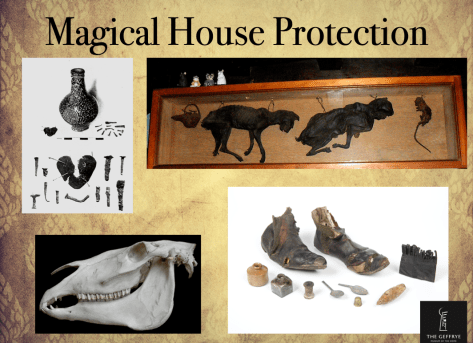

The objects and animals that people secretly tucked way into their walls and floors were knowns as apotropaics—items that ward against evil—and which acted as a layer of protection against all manner of supernatural dangers. There were numerous objects that have been found—placed where they were assumed to never been seen again—that have been uncovered by building crews and home DIY’ers. It does seem a shame to disturb these objects. They were quite important to the person who interred them and they operate as a sort of shrine that can feel wrong to dismantle; but when demolition must come, it is lucky that a few canny homeowners and builders choose to contact their local museum.

Old Shoes

Over the past sixty years, there have been various sustained studies carried out by Northampton Museum, with their Concealed Shoe Index, founded by June Swann, as well as work by folk historians Ralph Merrifield, Owen Davies, Ronald Hutton, Brian Hoggard, and chemist Alan Massey, among many others, into the practice of magical concealment.

While much of the collection is from the 19th century, they do have a few items on hand that prove home protection customs are still with us today. There are quite a few examples from the 20th century. A favourite of mine is a platform-shoe find that was hidden in 1970s.

Occult Objects?

In addition to these common objects, like shoes, there were other hidden items with a far more occult aspect. Under hearths and in walls, researchers have also found witch-bottles, dried cats, and horse skulls; all which were used to either ward off or distract the attention of evil spirits.

If you’ve travelled to old heritage homes in more rural areas, you might have come across witch wheels carved into the mantle piece of a fireplace.

I visited Milton’s Cottage in Chalfont Saint Giles last year with my partner and were delighted to come across—quite unexpectedly—witch wheels (also called ‘daisy wheels’ and ‘hexafoils’) carved onto the mantlepiece of Milton’s fireplace:

Some of the home-protection evidence that we find today can be traced back to medieval times, but for most of the artefacts, they are traced from the 17th century onwards. This is more a reflection of the survival of building materials than the true historical density in one period or another of these practices. However, the religiopolitical landscape of the 17th century cannot be ignored here.

Witch Panic

With the advent of the printing press, and the resulting mass sharing of frightening tales regarding witchcraft during this time, there was a heightened atmosphere of fear of witches and the harm they could inflict. This led to the popularisation of counter-witchcraft folklore, such as home protection practices. An atmosphere of fear would lead already vulnerable people to feel the need for not just physical home protection, but for spiritual protection as well.

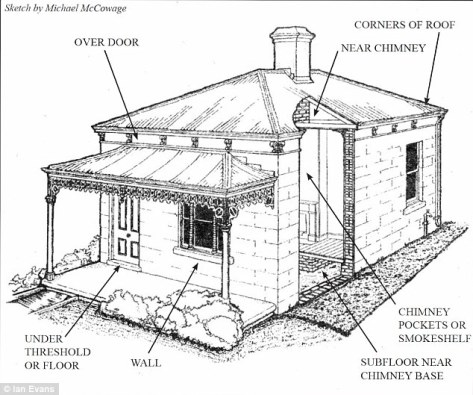

The stability of our homes is permeated by portals and voids, areas of vulnerability. The diagram above illustrates the common locations where home protection items have been found.

Throughout Swann’s research into concealed shoes, she found that voids around the hearth, fireplace, and chimney were by far the most popular. The focus on the hearth as a concentrated place of protection is understandable when we remember that the hearth was the centre of the home until later 20th-century heating made most rooms habitable in winter.

This focus on the open portals in our homes—the voids that are not protected by walls, such as window sills, door thresholds, and hearth/chimney spaces—suggests that people believed it was possible for dark forces to travel through the landscape and attack them by way of these vulnerable spaces. “Whether these forces were emanations from a witch in the form of a spell, a witch’s familiar pestering their property, and actual witch flying in spirit or a combination of all those is difficult to tell.” (Hoggard 15)

But witches were only one fearsome villain lurking out there in the dark. Additional sources of danger could also be restless ghosts, fairies, and demons. The nighttime landscape was full of dangers, and a home is only as secure as its most vulnerable portals.

Cunning Folk

Over the course of this research into home protection folklore, I began to wonder why the charms and practices used in the fight against witchcraft looked so much like witchcraft itself—and why these practices seemed to be used without fear in violently paranoid and toxic times.

Dividing the practices between witches and cunning folk is complicated a bit by the fact that cunning folk were themselves sometimes accused of witchcraft. “The term ‘cunning-folk’ was just one of several terms used in England to describe practitioners of magic who healed the sick and the bewitched, who told fortunes, identified thieves, induced love, and sundry tasks for their local community.” (Davies 2003 viii) The line between protection and threat was a fine one to tread—especially when a cunning person who couldn’t fix the community’s problems could be accused and turned from protector into sinister agent. (It makes you wonder why people would risk helping their neighbours at all if this is thanks they get for it, but maybe that’s just me.)

While there is plenty of evidence for the continued popularity of astrologers, fortune-tellers, and all sorts of occult practitioners well into the 20th century, for the most part people began to lose their fear of witches. And without witches, there became less need for cunning-folk.

It has been said that in uncertain times, people search for alternative sources of knowledge and divination to regain a feeling of control in their lives. Today, without the fears of church persecution or community-wide uniformity of belief systems, we now have the space to create our own rituals that make us feel safe.

Just as people today can define the space that they call ‘home’ in myriad ways, so too can we reinvent the ways in which we all can keep those home spaces safe—whether that’s through modern alarm systems, family dogs, or relearning the old ways of our cunning folk ancestors.

One theory posits that these home protection practices have not waned at all—rather that new buildings that have home protection trinkets tucked away in their crevices have no need to be demolished or have extensive repairs.

Yet.

Fifty, or maybe even one-hundred, years from now, when works begin to demolish and repair the buildings we craft today, perhaps a whole new cache of home protection totems will be found secreted within the walls, keeping us safe.

Further Reading:

Davies, Owen; Houlbrook, Ceri; ‘Concealed and Revealed: Magic and Mystery in the Home’, Spellbound: Magic, Ritual & Witchcraft, (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford) 2018. Book.

– Popular Magick: Cunning Folk in English History, (London: Hambledon Continuum) 2003. Book.

Davies, Owen, ‘The Material Culture of Post-Medieval Domestic Magic in Europe: Evidence, Comparisons, and Interpretations’, Boschung, Dietrich; Bremmer, Jan N. (editors), The Materiality of Magic, (Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink) 2015. Book.

Eastop, Dinah, ‘Outside In: Making Sense of the Deliberate Concealment of Garments Within Buildings’, Textile, Volume 4, Issue 3, p238-25. 2006. Journal.

Gazin-Schwartz, Amy, ‘Archaeology and Folklore of Material Culture, Ritual, and Everyday Life’, International Journal of Historical Archaeology’, Volume 5, Issue 4, p263-280. 2001. Journal.

Hoggard, Brian, ‘Witch Bottles: Their contents, Contexts, and Uses’, Physical Evidence for Ritual Acts, Sorcerty, and Witchcraft in Christian Britain, A Feeling for Magic, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan Publishers Limited) 2015. Book. p284-327

– Magical House Protection: The Archaeology of Counter-Witchcraft, (New York: Berghahn Books) 2019. Book.

Hutton, Ronald (editor), Physical Evidence for Ritual Acts, Sorcerty, and Witchcraft in Christian Britain, A Feeling for Magic, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan Publishers Limited) 2015. Book.

Pennick, Nigel, Skulls, Cats, and Witch Bottles: The Ancient Practice of House Protection, (Cambridge: Nigel Pennick Editions) 1986. Book.

Swann, June, ‘Shoes Concealed in Buildings’, Costume, Number 30, p56-69. 1996. Journal.

– ‘Shoes Concealed in Buildings’, Physical Evidence for Ritual Acts, Sorcerty, and Witchcraft in Christian Britain, A Feeling for Magic, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan Publishers Limited) 2015. Book. p364-402

Watkins, Carl (2004), ‘’Folklore’ and ‘popular religion’ in Britain during the middle ages’, Folklore, Volume 115, Issue 2, 2004, p140-150. Journal. DOI: 10.1080/0015587042000231246

Wingfield, Chris, ‘A case re-opened: the science and folklore of a ‘Witch’s Ladder’, Journal of Material Culture, Volume 15, Number 3, p302-322. 2010. Journal.

I just read your article (I was hosting for #folklorethursday) and wanted to tell you how much I liked it. The images and Further Reading section too. I would have loved to check out that old Pennick book but couldn’t find it anywhere!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I read Pennick’s book in the British Library, but it looks like you’re based in Canada. I would say that it isn’t a very long book, more like a pamphlet, so an involved hunt may not bring you enough pay off. My top books I’d recommend if you’re interested in this subject are the ‘Spellbound’ book from the exhibition of the same name at the Ashmolean in 2018 and Hoggard’s ‘Magical House Protection: The Archaeology of Counter-Witchcraft’. I hope that helps! 🙂

LikeLike

Hello there Sunshine, I came upon your website It’s Absolutely Fabulous!!!!! I Can’t wait till I have time to explore. Just wanted to say Thank you.

LikeLike